Model-free Load Control for High Penetration of Photovoltaic generation

I worked on a DOE funded project named SunShot during the last year of my thesis with OakRidge National Lab, TN, USA. The goal was to design a control algorithm that would help dissipate the solar energy uniformly accross different consuming HVAC units, while ensuring a certain temperature comfort inside the buildings. This would ultimately help maintain a certain stability of the grid.

Introduction

In this project we introduced a new model-free control (MFC) mechanism that enables the local distribution level circuit consumption of the photovoltaic (PV) generation by local building loads, in particular, distributed heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) units. The local consumption of PV generation will help minimize the impact of PV generation on the distribution grid, reduce the required battery storage capacity for PV penetration, and increase solar PV generation penetration levels. The proposed MFC approach with its corresponding intelligent controllers does not require any precise model for buildings, where a reliable modeling is a demanding task. Even when assuming the availability of a good model, the various building architectures would compromise the performance objectives of any model-based control strategy. The objective is to consume most of the PV generation locally while maintaining occupants comfort and physical constraints of HVAC units. That is, by enabling proper scheduling of responsive loads temporally and spatially to minimize the difference between demand and PV production, it would be possible to reduce voltage variations and two-way power flow. Computer simulations show promising results where a significant proportion of the PV generation can be consumed by building HVAC units with the help of intelligent control.

Model-free control with no PV tracking

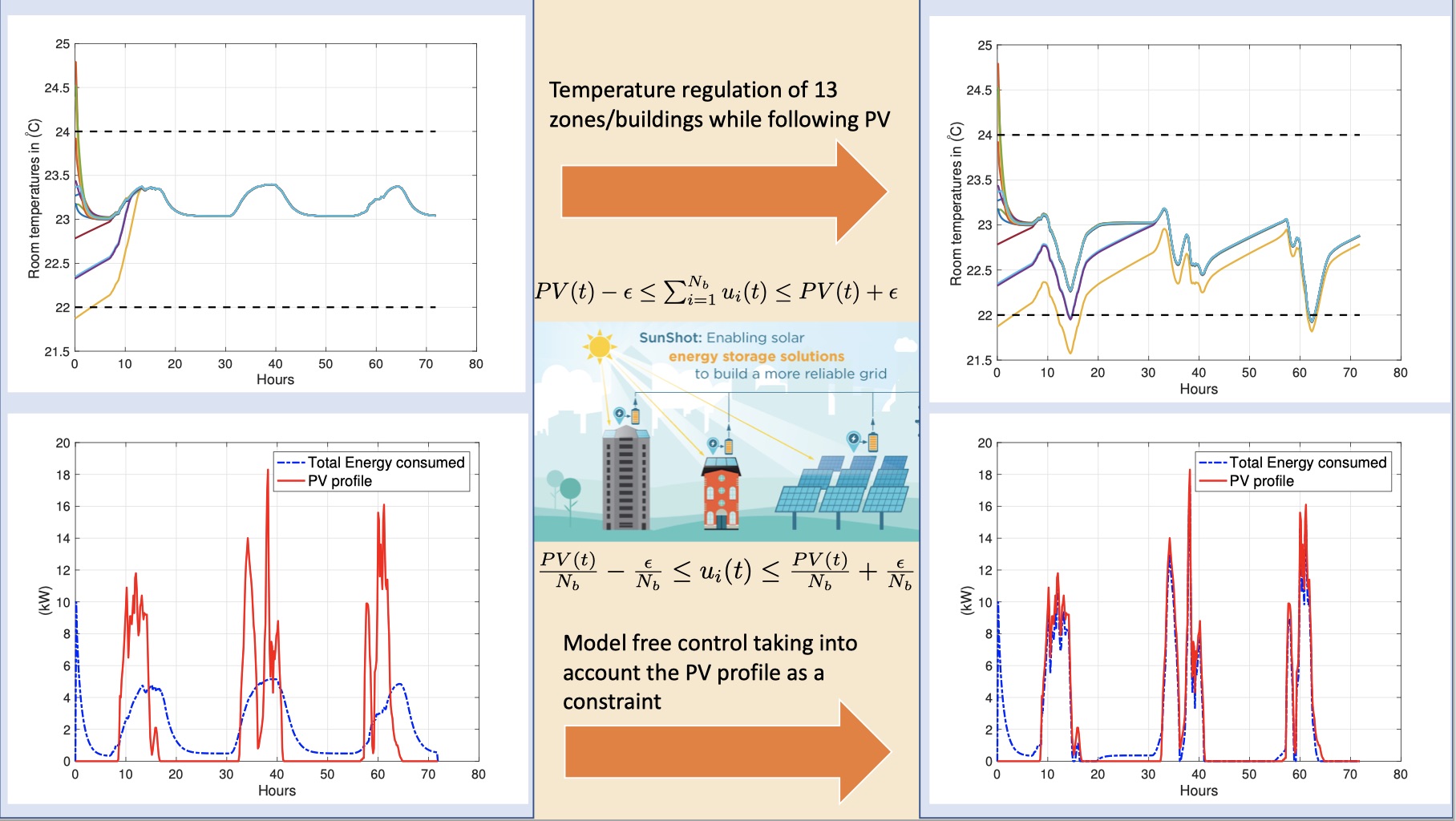

On the left-hand side of the above figure, one can observe the temperature’s variation inside 13 buildings, for a duration of three days. It is seen that the temperature is perfectly regulated. MFC is very efficient in rejecting outside disturbances: one can see their effect in the little bumps appearing essentially from the 8th to the 20th hour of the day. Note also that the initial temperatures in each building are different. The control inputs satisfy the required constraints. The initial large values correspond to the buildings with the highest initial temperature. It is important to notice that the total energy used by the HVAC units does not take into account the variations of the PV profile, hence, the large deviation of the total energy signal represented in blue dashed lines from the actual PV given in red solid line.

Simulation with PV profile

The right-hand side of the figure displays the time evolution of the interior temperature for 13 buildings while the PV tracking is taken into account. Note that most of the temperatures are within their prescribed comfort zone. The slight violation of the lower constraints for one or two buildings is due to the tight restriction on the PV tracking since the constant epsilon = 1, i.e., a rather narrow tolerance margin. Temperatures where slight overshoots appear are those that are starting from the lowest initial temperatures. By imposing more energy consumption for the buildings than necessary for regulating its indoor temperature, one would expect the HVAC units to run during more time or with higher intensity. It would yield large variations. This behavior is rather normal. It can be significantly improved by selecting an appropriate number of buildings. It is important to understand the difficulty of the actual compromise between the requirement of imposing a certain level of comfort inside the buildings, and that of closely following the generated PV signal. Those two requirements are very often contradictory. Our viewpoint helps in satisfying both control objectives without the need of any complex optimization procedure, especially if one has to deal with a nonlinear model. As an initial study we decided to focus on a limited number of HVAC units to assess our results. However scaling the problem to larger building units is straightforward. It does not necessitate any change in the problem formulation. More importantly it will not require any additional significant computational power. s More mathematical details on the approach can be found on the conference paper [C8] that can be consulted on my publication post.